“He was a bold man that first ate an oyster,”

Opined Jonathan Swift, the satirist whose writing four centuries ago displayed biting wit. Many would agree that the homely bivalve is not an object of conventional beauty. Its beauty comes from its fresh, briny taste that carries the essence of the sea.

Once, conventional wisdom dictated that oysters only be eaten in months with R in them. That time is long past. Oysters are a

year-round delicacy from coast to coast, though summer-harvested bivalves simply don’t taste as good as the cold-weather, cold-water sorts.

Oysters were once so abundant on American shores they were known as the “poor man’s fish.” Oysters were drastically afflicted by over-harvesting, predators, and pollution, but now, long-time oystermen and newbies too are farming oysters responsibly. Currently, this aquaculture crop is cultivated and harvested and is a delicacy. There are scores of varieties, from the Apalachiocola of the shallow waters off the Florida Panhandle to the Zen oysters from the deep waters of the British Columbia coast. Oysters fall into five broad categories. Pacific oysters are the world’s most cultivated variety. Kumamotos, originally from Japan, are now raised both there and on this side of the Pacific Ocean. Tiny Olympic oysters are native to the Pacific Northwest. European Flats originated in France, where the most famous variety is the Belon — a type now gaining favor on the East Coast too.

Dining Out on Oysters

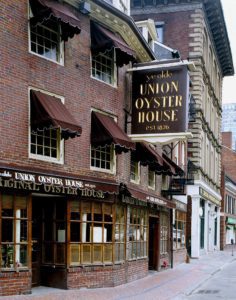

Restaurants in this country have been serving oysters for nearly two centuries. Boston’s Old Union Oyster House, a National Historic Landmark, has been shucking and serving these magnificent mollusks since 1826. Alciatore Antoine immigrated from Marseille to the young United States in the early 19th century. In 1840, he opened Antoine’s in New Orleans, where he created a decadent dish called Oysters Rockefeller — served on the half-shell, topped with spinach or other greens, butter and breadcrumbs and baked or broiled.

When the respected website Eater New York-listed restaurants popular with tourists but appealing to fussy locals as well, New York’s Grand Central Oyster Bar was on the shortlist. It opened in 1913 and is the city’s best-loved mecca for oyster lovers. Its oyster stew is the stuff of legend.

The Walrus & The Carpenter in Seattle’s Old Ballard ‘hood has been packing ‘em in since it opened in 2010. By that time, Casamento’s in New Orleans had been serving oysters for nine decades. Their char-broiled oysters are faves.

P&J Oyster Company is a family business in New Orleans tracing its roots back to

1876. The family-owned company cultivates and harvests oysters at the mouth of the Mississippi and ships them out of an old warehouse in the French Quarter. It has published The P& J Oyster Cookbook, known equally for its beautiful photographs and its recipes.

The Hog Island Oyster Company farms oysters in Tomales Bay in northern California. It operates a bay-view seafood bar right on the water, as well as a popular, full-service restaurant in San Francisco’s Ferry Building. The view is of the Bay Bridge and the oysters are just as fine as those up the coast.

“Oysters are the most tender and delicate of all seafoods.

They stay in bed all day and night. They never work or take exercise, are stupendous drinkers, and wait for their meals to come to them,”

wrote Hector Bolitho in The Glorious Oyster.

Tamar Haspel and Kevin Flaherty are relative newcomers to oystering. They are cottage farmers on Cape Cod, where they started raising their own chickens, catching their own fish, growing their own tomatoes and hunting for their own venison, and they now operate an oyster farm where they grow about 50,000 oysters a year in the beautiful coastal waters.

The bottom line, though, for all of us is the sheer appreciation of oysters. Whether you slurp ‘em raw at a seaside shack, delicately dine on them in a fine restaurant or toss ‘em on the grill, oysters are improbably delicious. One more thing: Don’t expect to find any pearls.